What a week it was…

I haven’t even started writing this edition yet, but I know it will be longer than usual. If you only have a bit of time to get updated, here are the main takeaways:

The Federal Reserve left the federal funds rate unchanged, signaling that they will complete their tapering of asset purchases in March 2022. The next steps will be rate hikes, then reducing the size of their balance sheet. Markets are now pricing-in five rate hikes in 2022, compared to three at the start of the year.

Q4 GDP results show annualized real growth of +6.9%. An increase in private inventories was the primary driver of the increase, contributing +4.9%. One of my pet peeves in economics is how GDP data is reported as annualized data, instead of calculating the year-over-year (YoY) or quarter-over-quarter (QoQ) change. In order to calculate how much real GDP changed from Q3 2021 to Q4 2021, we can solve the following calculation:

[(1.069)^0.25] - 1 = 0.0168 = 1.68%. THAT’S how much GDP actually changed, whereas, the +6.9% headline figure is how much the economy WOULD grow if we annualized the quarterly growth rate.

Personal consumption expenditures (PCE), the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation, for December 2021 was released. The headline number was +5.8% on a 12-month basis, while the core figure was +4.9%. Both figures came in higher than estimates, reaching levels unseen since 1983.

The stock market had the choppiest week I’ve experienced in my 8-year involvement with markets. On Monday, the S&P 500 did something that’s only happened three times since 1977. Relative to last week’s closing price, the S&P 500 was +0.79%. Despite a seemingly bland week at face value, the S&P 500 fluctuated between $4,222 and $4,453 all week.

Economy:

The economic data released this past week certainly dominated the news cycle & was the catalyst for market moves. There were three major aspects:

The Federal Reserve’s FOMC policy decision meeting/announcement on Tuesday & Wednesday.

Q4 2021 GDP data on Thursday.

Personal consumption expenditures for December 2021 on Friday.

Much of the panic in markets over the past several weeks has been caused by an aggressive tone from the Federal Reserve and continued increases in inflation. As a consequence of these dynamics, we’ve seen nominal yields rise and stock market prices move lower. The three events listed above had massive implications for yields, which helps to explain why the stock market had such a wild week.

Let’s address each of these three aspects chronologically:

To no major surprise the Federal Reserve kept interest rates unchanged, with the target federal funds rate between 0.00% and 0.25%. All focus continues to be on the rate of tapering, the timeline for rate hikes, and the frequency of rate hikes going forward. As it pertains to the rate of tapering, and specifically when the tapering process will end, the Federal Reserve expressed that March 2022 is their target date of completion. The Fed didn’t commit with any certainty on when rate hikes will begin or how many they will do in 2022.

In the press conference immediately following the policy announcement, Jerome Powell stated very clearly that the U.S. economy no longer needs sustained high levels of monetary policy support. Shortly thereafter, Powell stressed that “there is quite a bit of room to raise interest rates”. As I’ve been saying for months, the inflation data has warranted an increase in rates for quite some time, and the employment data has improved substantially towards maximum employment. With these criteria being met, it’s quite probable that the Fed is behind the curve and will be required to play catch-up. The Fed is now forced into reactive policy instead of proactive policy.

Next, the Q4 2021 GDP data was released on Thursday morning. Considering that the Federal Reserve announcement was decisively hawkish, there was a lot of pressure on the GDP data to be strong. Essentially, if the Fed was committed to raising rates, doing so in a deteriorating economic environment would be dangerous. The data came out stronger than expected, showing real GDP growth of +6.9% at an annualized rate. As I mentioned in the summary at the beginning, I believe there’s a major flaw in how GDP data is reported relative to how other economic data is reported. I explained this in a Twitter thread:

I think my biggest pet peeve in economics is reporting GDP as an annualized number. Why can't it just be reported as a quarter-over-quarter increase or relative to level of economic activity 12-months ago?

Q4 2021 GDP growth of +6.9% annualized = +1.68% relative to Q3 2021.

It's just an odd thing to "forecast" variable growth in an annualized fashion. For CPI & inflation, we look at the month-over-month and the year-over-year (TTM) change. This feels correct. We don't take the MoM delta, then compound it by 12.

Why do we do this for GDP?

We can still calculate the quarter-over-quarter change in GDP by simply doing the following calculation: (1.069)^0.25 = 1.0168 = +1.68%.

Generally speaking, the GDP data was impressive, particularly considering that government spending contracted relative to Q3 2021. For me personally, I want to see genuine economic growth coming from the private sector, not from government which is financed by taxes and debt-issuance.

The primary concern I had over the GDP data is that the major driver of the +6.9% annualized figure was from a meteoric increase in private inventories. What does that mean exactly? That businesses were stocking up on inventory, likely due to concerns around supply chains bottlenecks, port congestion, and holiday shopping. In order to be proactive around these concerns, businesses invested substantially in building up their inventories. First of all, that’s a good thing as it reflects the ability of businesses to remain flexible and allocate capital accordingly. As it pertains specifically to GDP however, we don’t necessarily want to see the bulk of growth coming from businesses taking preventative measures to meet potential demand. After all, according to data from Liz Ann Sonders, consumer spending contributed +3.3% to the top-line growth of +6.9%.

There was one other major concern I focused on regarding the GDP data. According to the press release:

“Disposable personal income increased $14.1 billion, or 0.3 percent, in the fourth quarter, compared with an increase of $36.7 billion, or 0.8 percent, in the third quarter. Real disposable personal income decreased 5.8 percent, compared with a decrease of 4.3 percent.

Personal saving was $1.34 trillion in the fourth quarter, compared with $1.72 trillion in the third quarter. The personal saving rate—personal saving as a percentage of disposable personal income—was 7.4 percent in the fourth quarter, compared with 9.5 percent in the third quarter.”

The takeaways from this are extremely simple:

Disposable personal income is increasing at a decreasing rate. More simply, it’s decelerating. If we adjust disposable personal income by the rate of inflation, it’s decreasing by -5.8% vs. -4.3% in Q3 2021. This means that real disposable income is declining at an accelerated rate. That’s not a great sign.

U.S. households are dipping into their savings in order to consume, pay-off debts, etc. Likely due to inflation, households are saving less as a portion of their personal disposable income. Again, not a great sign.

Combining points 1 & 2, income and wealth are declining and/or decelerating.

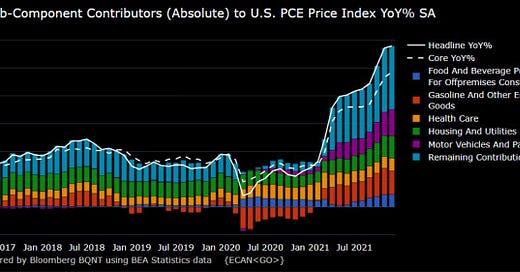

Last but not least, the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) data was released, showing a continued acceleration in inflationary pressures in December 2021. The headline PCE figure was a 12-month increase of +5.8%, while the core PCE (which excludes food & energy prices) increased by +4.9%. The last time either data point was this high was in 1983. Many U.S. consumers are facing the largest inflationary pressures of their lifetimes. This reaffirms that the Fed is now forced to be reactive instead of proactive.

Per data from Michael McDonough, here is the PCE data with insights on each of the underlying components:

At the beginning of the week, markets were pricing-in three rate hikes for 2022. By the end of the week, markets had adjusted to expect five rate hikes in 2022. The freshest updates from the banks echo the increase in rate-hike expectations:

In totality, it was an extraordinarily important week for economic data. GDP growth and PCE inflation data came in higher than expectations, but generally confirmed existing trends: slight deceleration in economic activity & continued acceleration in inflation. The Fed’s posturing to fight inflation, while still providing strong levels of stimulus, is reminiscent of a dog barking at the mailman. The mailman has yet to see whether or not it’s a Rottweiler or a Chihuahua.

Stock Market:

It’s no secret that this week was a rollercoaster of action in the stock market. It literally got started on Monday with a historical session, in which the S&P 500 was down -3.99%, but managed to flip positive and close +0.29% on the day. Per Jim Bianco, this was only the third time it’s happened since data started to be recorded in 1977:

Upon each of the three major economic news events listed above, markets had significant reactions in both directions. Each day seemingly lost all of the morning’s gains, or managed to reverse all of the morning’s losses. It was a market environment unlike anything I’ve ever experienced, swinging in both directions with extreme indecision. When the market seemed to move with conviction in one direction, suddenly it would whipsaw the other way.

For the week, the major U.S. indexes performed as follows:

• Dow Jones Industrial Average ($DJX): +1.36%

• S&P 500 ($SPX): +0.77%

• Nasdaq-100 ($NDX): +0.13%

• Russell 2000 ($RUT): -0.96%

Sarah Ponczek from UBS’s wealth management division shared some great data since the S&P 500 has officially crossed below a -10% drawdown from the ATH’s.

I know there’s a lot of data in this table, but let’s just purely focus on the average data, particularly on the four right-side columns.

The forward-looking returns after experiencing a drawdown between -10% and -20% are rather optimistic! On average, the 12-month rate of return is +17.7%. It’s important to note that this data is only for declines between 10-20%, so it’s tuning out occasions like the Great Recession and the COVID crash. Regardless, there are reasons for medium & long-term optimism based on this chart while also acknowledging that things could get worse in the short-term.

Talk soon,

Caleb Franzen